A worldwide crackdown on vaping is well under way, but what exactly is under the lid of the disposable kind that have borne the brunt of most fresh regulations on the products?

One team of experts has looked in to just that, taking apart disposable vapes for everyone to see exactly what there is underneath the metaphorical bonnet.

It comes as the UK prepares to ban disposable vapes, with Prime Minister Rishi Sunak setting out the new measures at the start of 2024.

Advert

Regardless of who wins the general election, both Labour and the Conservative parties have committed to making this measure a reality, with it set to become law by 2025.

The same goes for smoking for everyone under the age of 15.

It comes as Australia has gone further in its crack down on vaping, with it the first country to ban the sale of vapes altogether outside of pharmacies.

A new law means that the domestic manufacture, supply, commercial possession and advertisement of disposable and non-therapeutic vapes are banned across the country. You can only get vapes from behind the counter at a pharmacy with a prescription needed to buy a therapeutic vape.

And to coincide with the ban, experts at the University of New South Wales (UNSW Sydney) have taken apart vapes so people can see exactly what is in the disposable kind.

Led by Dr Miles Park, a senior lecturer in Industrial Design, he says: "Currently, the most predominant vapes on the market are single-use, disposable products designed to appeal to younger people.

"Despite their short lifespan, vapes are complex products that contain several valuable resources.

"However, there are no practical means to collect or recycle vapes. Most end up as electronic waste or e-waste in landfill. Some are simply thrown on the street as litter. So what’s really inside vapes?"

Obviously, the first thing found by Dr Park is the casing, which is often aluminium in nature with plastic coverings on both ends.

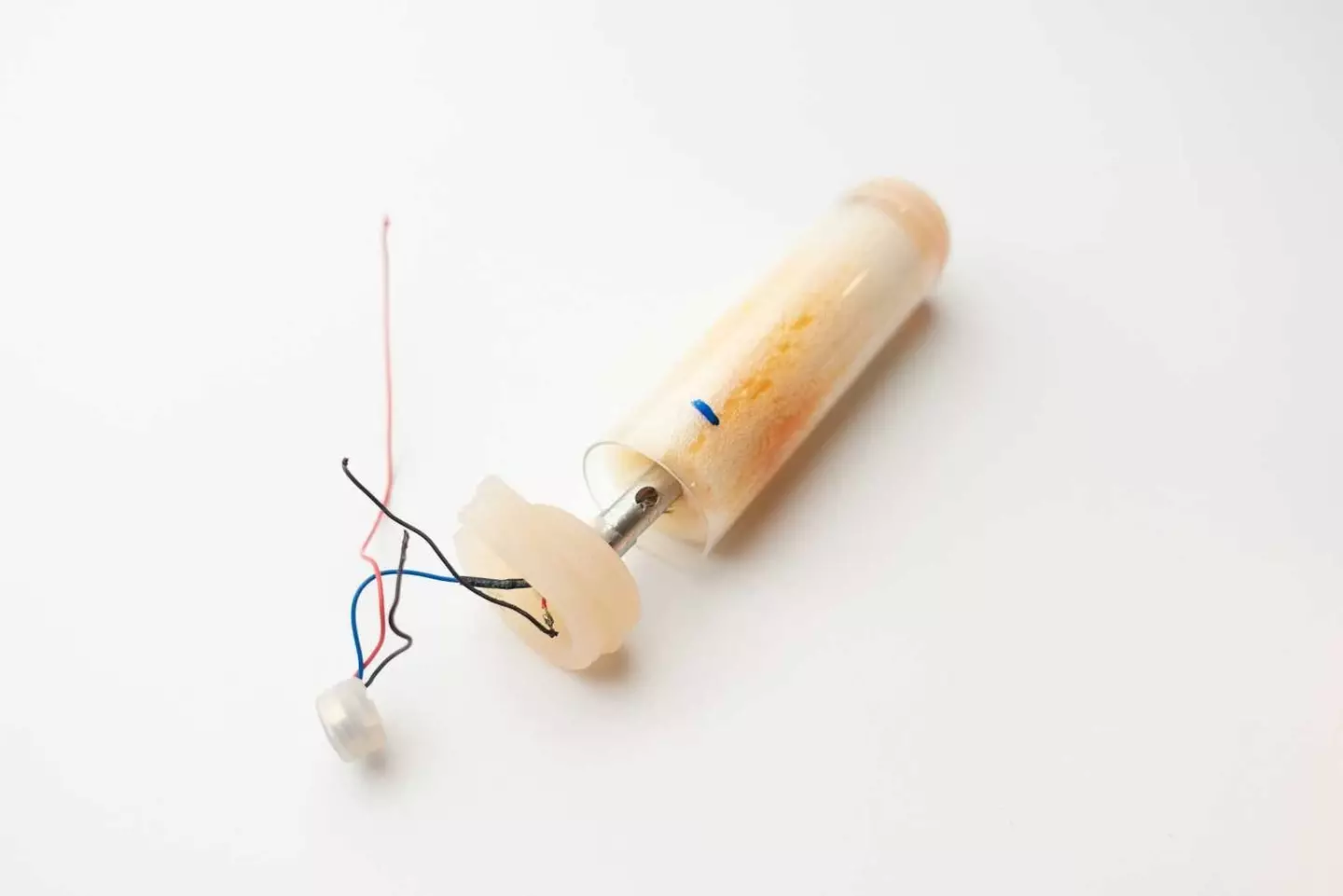

"Once the housing end caps are removed, which is often not a straightforward task, the internal assembly slides out. These internal parts are wedged or taped together within the main housing, and battery terminals are soldered to wires connecting to a pressure sensor and a heating element embedded in an e-liquid reservoir," he says.

Disposable vapes then come with a non-rechargeable, with the one taken apart by Dr Park being lithium. Basically, a smaller version of the kind you use in a drill or even an electric car.

He said: "These cells have high-power density: they can store lots of electrical energy in a relatively small package.

"This is needed to supply periodic bursts of energy to the heating element, and to outlast the supply of e-liquid in the reservoir.

"All the batteries we tested during the teardown of depleted single-use vapes still maintained a charge that could power a test light bulb for at least an hour."

Dr Park then found something called a pressure sensor, which works when you take a drag of the vape and supplies a temporary heating element.

There's then also a heating element with a vaporiser, which turns the e-cigarette liquid in to vapour before it is inhaled.

And obviously, there is also the e-liquid container or 'reservoir' as it is called, which is a plastic tube with silicone caps on either end.

"The e-liquid itself contains a range of ingredients such as propylene glycol, nicotine and flavourings, many of them with unknown health impacts," Dr Park says.

Dissecting the vape left Dr Park with one clear message - they are not good for the environment, pose a large fire risk for those working landfills, and even have toxic impacts on the environment.

He said: "Having potentially valuable metals mixed with other, low-value materials such as plastic makes vapes difficult to separate and recycle.

"Overall, single-use vapes are clearly wasteful of resources and dangerous in the environment."

Topics: Vaping, Health, UK News, Australia, Education, Science, Technology, World News