Around half a million Brits suffer from inflammatory bowel disease (IBD), an umbrella term from Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis.

Crohn's disease can affect any part of the digestive tract, while ulcerative colitis causes inflammation of the large intestine.

The symptoms of IBD include stomach pain, diarrhoea, a sudden need for the toilet, blood in what comes out when you're on the toilet, weight loss, fever and a lack of appetite.

Symptoms can also take a toll on your mental health, with anxiety and depression both being linked to inflammatory bowel disease as well.

Advert

In short, it's an absolutely horrible thing to live with, and a woman who has IBD has explained what the absolutely worst thing about this smorgasbord of s**t is.

Perhaps fortunately then, the cause of inflammatory bowel disease has been discovered by scientists in the UK in what could be a major breakthrough for a condition which affects around 500,000 Brits and a lot more people elsewhere in the world.

A study from Francis Crick Institute and University College London found that existing drugs seem to reverse IBD in cells and samples of patients.

Researchers are now working out how to make this medication specifically target the cells they'd need to tackle to deal with the likes of Crohn's disease and ulcerative colitis.

Advert

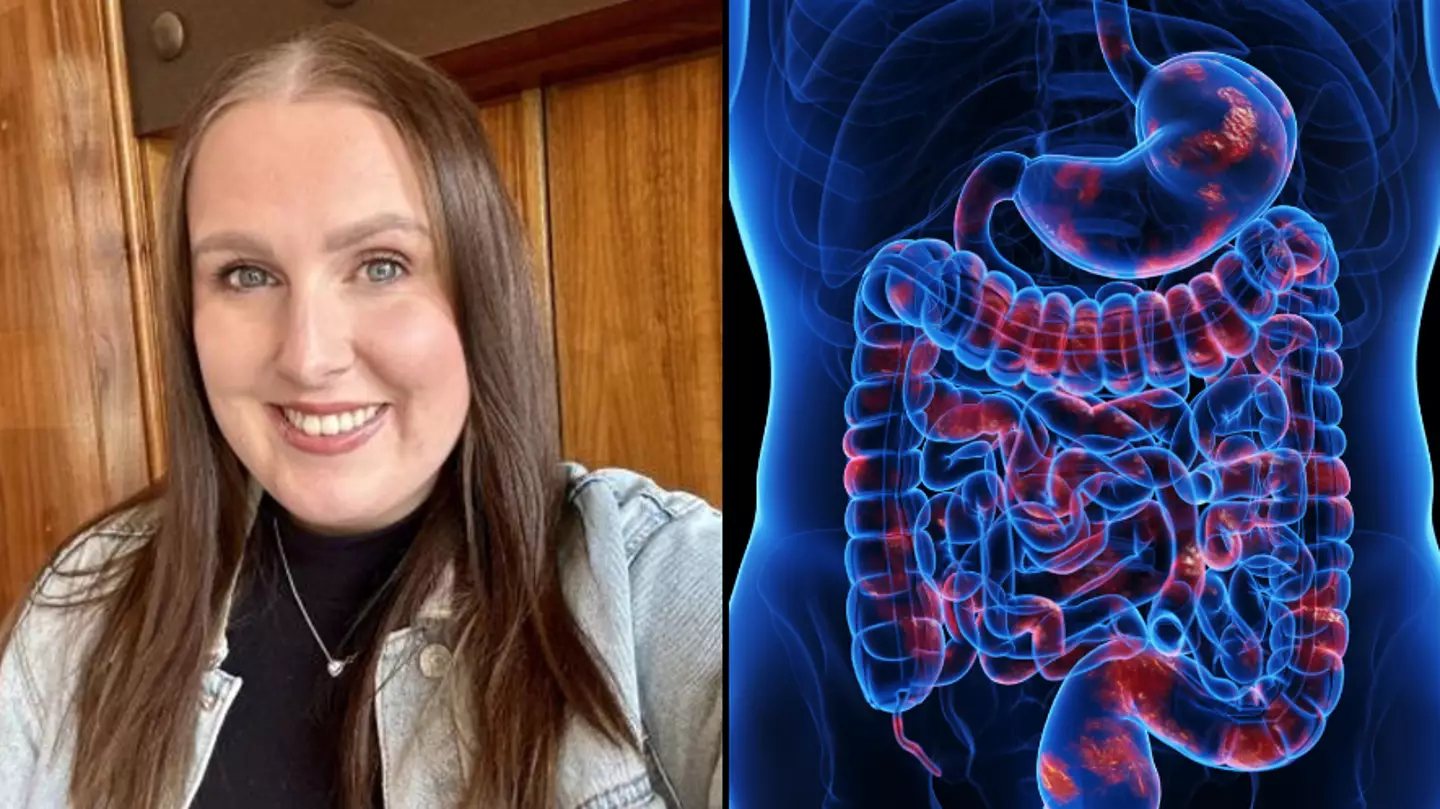

27-year-old Lauren Golightly was diagnosed with Crohn's in 2018 after developing stomach cramps and finding blood in her stool.

As you might imagine, she's a big fan of this news.

"Crohn's has had a huge impact on my life. I've had a rocky road since diagnosis, with many hospital admissions, several different medications and even surgery to have a temporary stoma bag," she said, before moving on to discuss the worst thing about it.

"One of the hardest things about having inflammatory bowel disease is the uncertainty around it.

Advert

"I still experience flare-ups and can still spend quite a bit of time in hospital. Learning about this research is so exciting and encouraging.

"I am hopeful this could potentially make a difference for myself and so many other hundreds of thousands of people living with IBD."

This latest development has been dubbed a 'holy grail' discovery and it's hoped that clinical trials on humans could begin at some point in the next five years.

Some work is still to be done on the existing drugs we have, but it's a big step in the right direction.

Advert

James Lee, group leader of the Genetic Mechanisms of Disease Laboratory at the Crick, and consultant gastroenterologist at the Royal Free Hospital and UCL, who led the research, said: “IBD usually develops in young people and can cause severe symptoms that disrupt education, relationships, family life and employment. Better treatments are urgently needed.

“Using genetics as a starting point, we’ve uncovered a pathway that appears to play a major role in IBD and other inflammatory diseases.

“Excitingly, we’ve shown that this can be targeted therapeutically, and we’re now working on how to ensure this approach is safe and effective for treating people in the future.”