Something odd happened to mice that were sent into space to experience microgravity.

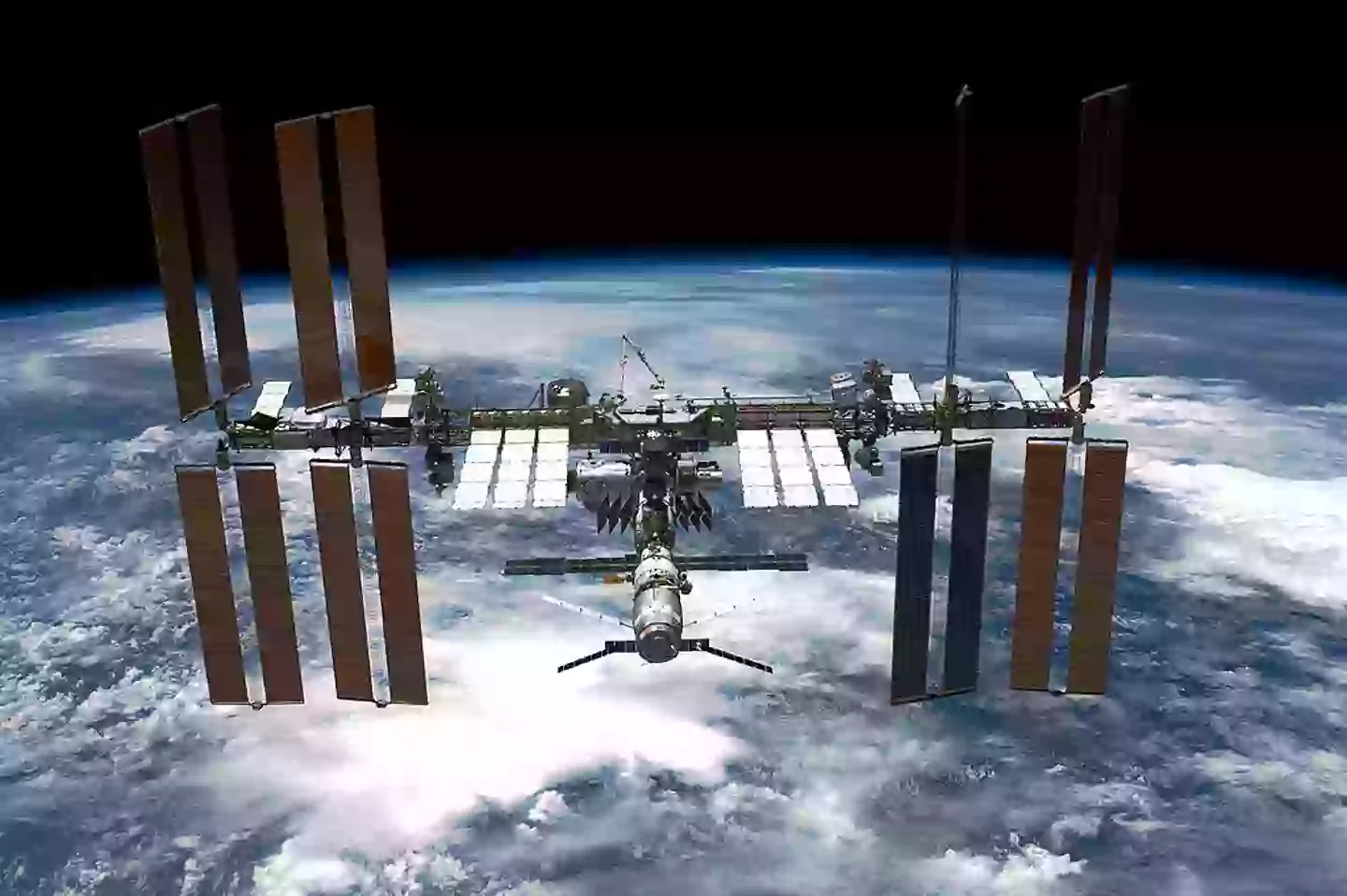

Back in 2019, NASA released their observations from studying the behaviour of mice aboard the International Space Station (ISS) for the public to see, as well as a two-minute clip of the animals on YouTube.

This year, they have followed up this initial research with a scientific paper of mice that spent 37 days aboard the ISS.

Space is an unforgiving environment, and being up there for prolonged periods of time can take its toll on the body - just ask Suni Williams and Butch Wilmore.

Despite it being over 60 years since mankind experienced spaceflight for the first time, space agencies are still taking every opportunity possible to study the effects of being space to better inform future missions.

With the likes of Elon Musk aiming to send humans to Mars by the 2030s at the very least, our understanding of the long-term effects of microgravity are essential.

Staying aboard spacecrafts such as the ISS for long periods of time can take its toll (NASA via Getty Images) But what is microgravity?

Basically, it's a very weak form of gravity, which can be experienced in an orbiting spacecraft.

NASA stated in their 2019 report that they are 'preparing to send astronauts on journeys that will include longer stretches in microgravity – to the Moon and onward to Mars.'

So, their understanding of 'basic biology' in space is essential in helping astronauts adapt and thrive.

The use of other organisms, such as mice, who share similarities to the human body system, can be used to do more research in the 'weightless' microgravity environment.

In their 2025 paper, the focus was on bone loss, or more specifically, its density, and how radiation in space can affect it.

It was estimated by the space agency that for every month in space, the density of weight-bearing bones drops one percent, a large amount that is followed by a loss of 20 percent muscle mass in under two weeks.

The work focuses on female mice, and how their bones fared, compared to those on Earth in regular vivarium cages, and in an ISS environmental simulator.

Results revealed that bone loss wasn't uniform, and was specific to the sites that were loaded from weight.

The femurs of mice in space showed more bone loss than spines, and it is suggested that this is due to microgravity and not due to the higher levels of radiation.

The process by which bones lost mass differed in previous experiments involving medaka fish that were sent to the ISS.

Essentially, bone re-sorption cells work overtime, and in space, this was clear with the fish, which saw their bone-forming cells take a back seat.

But these new findings suggest that it isn't that simple, with different types of bones faring differently in the microgravity environment.

There's no clear formula when it comes to bone mass increasing/decreasing in space (YouTube/NASA) While weight-loaded bones such as the femur lose mass, others would stay the same, while cranial bones get denser, among other types.

It could be caused by the increase in blood pressure in the upper part of the body, as the first few days in space can make the face swell, causing headaches and affecting sense of smell.

When the body starts to get rid of blood, this can stop.

So, while new discoveries have been made, there's still work to be done to get a definitive answer on how human bones will react to extended periods of time in space.

Joshua Nair

Joshua Nair