A man who experienced astonishing side effects after living in an underground cave did the unthinkable by going back to spend another six months down here.

Given the fact that our lives are heavily regimented by a 24-hour cycle, living with the complete absence of time sounds pretty jarring — or even torturous. But for French explorer Michel Siffre, secluding himself underground in a cave wasn't a nightmare scenario but instead a fun experiment.

So fun that after emerging from his two-month subterranean sabbatical in 1962 he decided to head on back down there for a whopping six months in 1972.

Here is what he was able to discover about the human body and it's internal body clock.

Advert

Michel Siffre's 1972 cave experiment

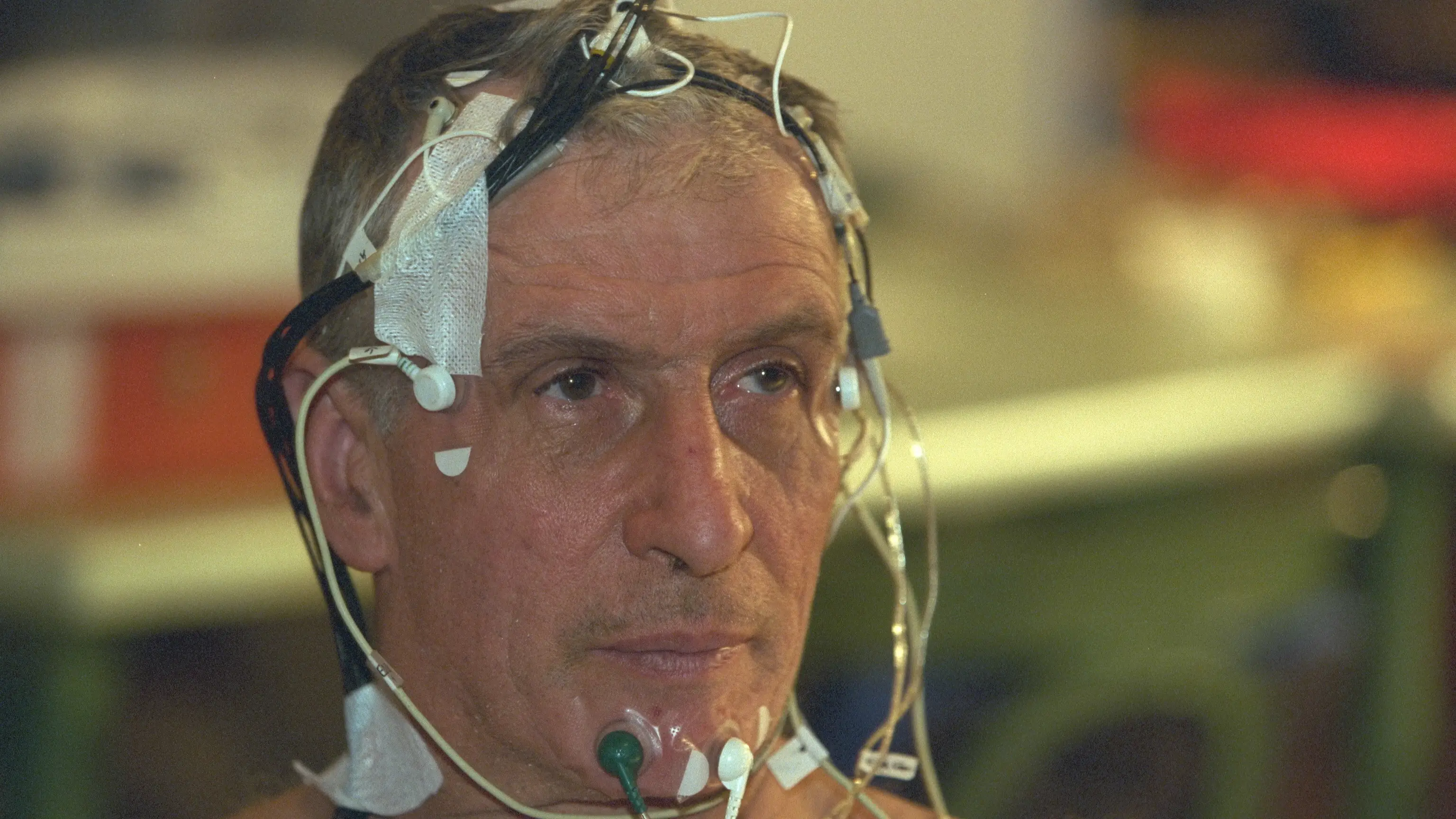

In 1972 Siffre, then aged 33, made the decision to spend six months living in Midnight Cave, Texas. Like his previous 1962 experiment, the hypothesis was simple: what impact does time have on the body and it's human circadian rhythms (our internal body-clock)? And, once deprived of an external indicator of time, would the body's sleep-wake cycle be impacted?

And it was here that the field of human chronobiology was formed.

What were the aims of Siffre's experiment?

Like his first experiment, Siffre would retreat into the cave with limited communication to the outside world, he was able to contact the team monitoring him but not vice versa, and conduct various experiments while being watched.

Daytime would be determined whenever Siffre woke-up and he slept whenever he felt the need to.

Explaining his decision to head back underground a decade after his initial experiment during an interview with a 2008 interview with Cabinet Magazine, the explorer said he wanted to understand if there were any changes in how his 'brain perceives time' since his first experiment and the '48-hour sleep/wake cycle'.

"I decided I would stay underground for six months to try to catch the forty-eight-hour cycle," he said.

What did Siffre discover during his six months underground?

Siffre would indeed succeed in catching the elusive 48-hour sleep wake cycle during his second underground excursion, although not regularly.

"There were two periods where I caught the forty-eight-hour cycle—but not regularly," he said. "I would have thirty-six hours of continuous wakefulness, followed by twelve hours of sleep."

Perhaps more interesting is the fact that Siffre wasn't able to tell the difference between the longer and shorter days he experienced in the cave.

"There was no evidence that I perceived those days any differently. Sometimes I would sleep two hours or eighteen hours, and I couldn’t tell the difference," he added.

The experiment would also have negative impacts on Siffre's mental wellbeing, which began to deteriorate during his time in the cave.

During a 1975 recollection of his experience, Siffre the Frenchman explained feeling a sense of overwhelming 'lethargy and bitterness' due to isolation.

The moral of the story? Humans cannot understand time without external stimuli and that being alone underground is very boring.