Scientists say they've developed the 'world's largest family tree' linking together a mega 27 million people around the globe.

The new genealogical network was developed at the University of Oxford with 'unprecedented detail' and will hopefully give scientists more of an understanding about the evolution of the human race.

It's being said that the study might also help with medical research focusing on the origins of disease, with regards to identifying genetic predictors, reports the Daily Mail.

Advert

The project has been published today in the journal Science by researchers from the University of Oxford’s Big Data Institute.

"We have basically built a huge family tree, a genealogy for all of humanity that models as exactly as we can the history that generated all the genetic variation we find in humans today," said study author and evolutionary geneticist Dr Yan Wong.

"This genealogy allows us to see how every person’s genetic sequence relates to every other, along all the points of the genome.

"While humans are the focus of this study, the method is valid for most living things; from orangutans to bacteria.

Advert

"It could be particularly beneficial in medical genetics, in separating out true associations between genetic regions and diseases from spurious connections arising from our shared ancestral history."

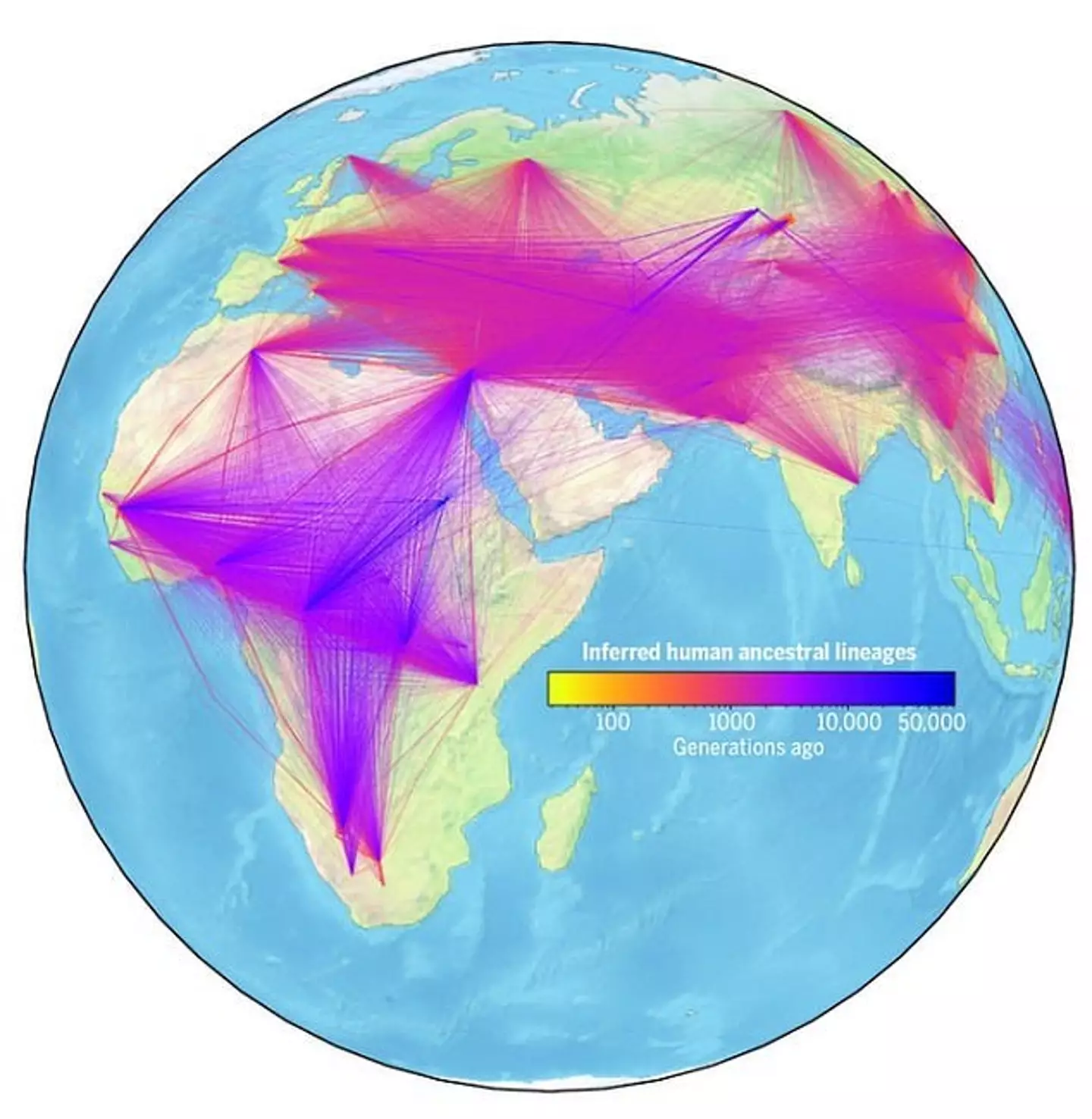

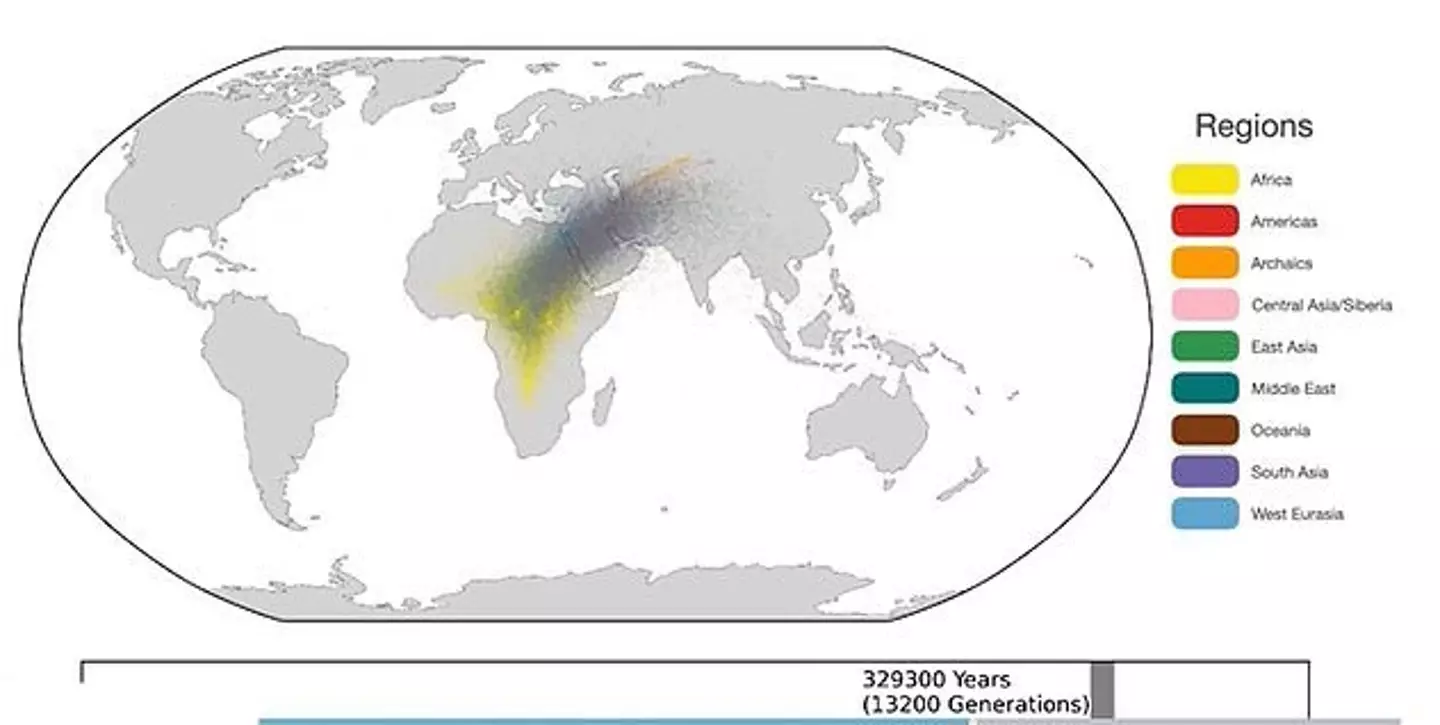

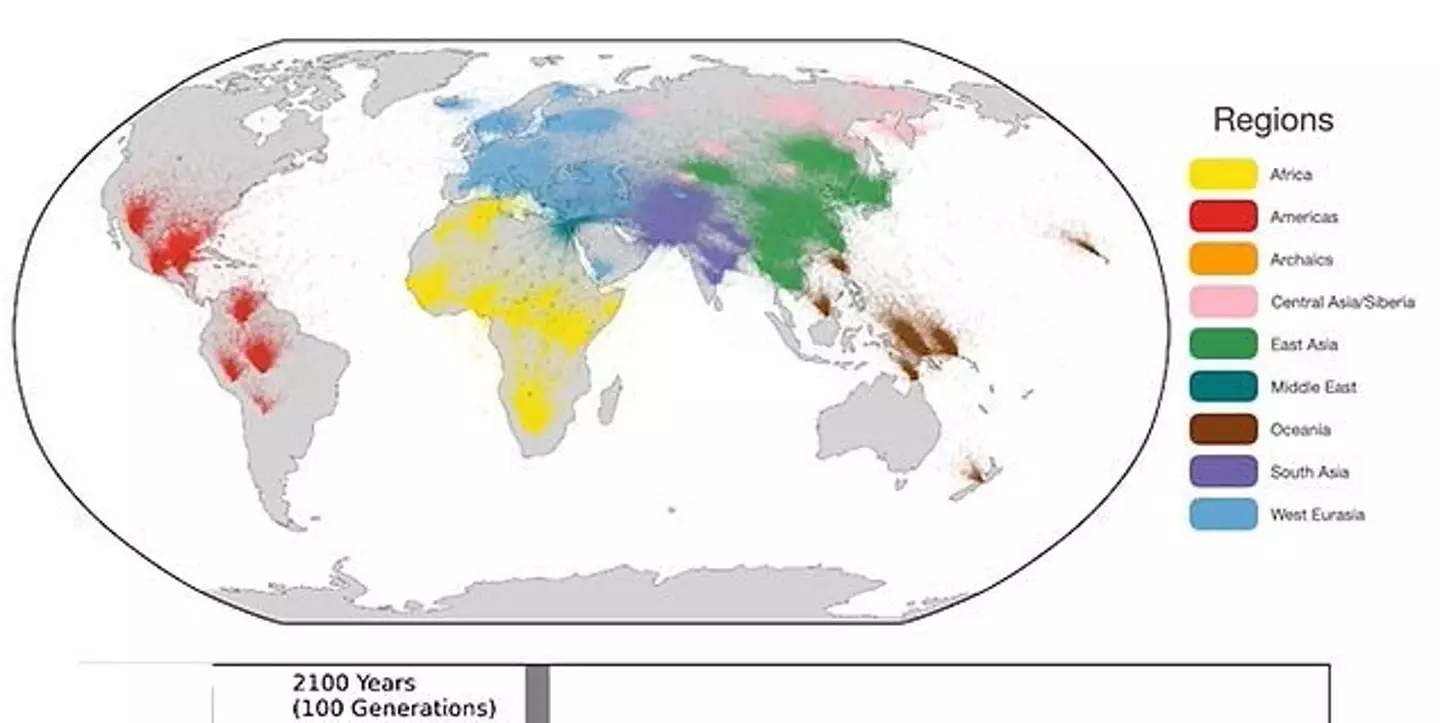

The team claim that the possibility of learning more about the origins of human genetic diversity might help produce a map of how people all around the world are related to one another.

More specifically, the new method is able to take on huge amounts of data from multiple news sources.

How it works is, the study integrates data on modern and ancient human genomes from eight different databases.

It includes a total of 3,609 individual genome sequences from 215 populations.

Advert

The ancient genomes uses all sorts of samples found across the world with ages ranging from 1,000s to over 100,000 years.

"Essentially, we are reconstructing the genomes of our ancestors and using them to form a vast network of relationships," said lead author Dr Anthony Wilder Wohns, who now a postdoctoral researcher at the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard.

"We can then estimate when and where these ancestors lived.

"The power of our approach is that it makes very few assumptions about the underlying data and can also include both modern and ancient DNA samples."

Topics: Science