A man suffered one of the most brutal silent deaths ever when he made a daring attempt to reach the bottom of a famous sinkhole.

Zacatón is technically known as a cenote, essentially a sinkhole, and is located in the north east of Mexico, an area that has become popular for divers to explore since the landowner granted permission for diving in 1990.

Jim Bowden and Gary Walten were the first inside the cenote, and thought they found its depth after dropping a plumb line and seeing it stop at 250 feet (76m), though this was just a platform, and its real depth was a terrifying 1,112 feet (339m) deep.

It is the deepest cenote in the world.

Advert

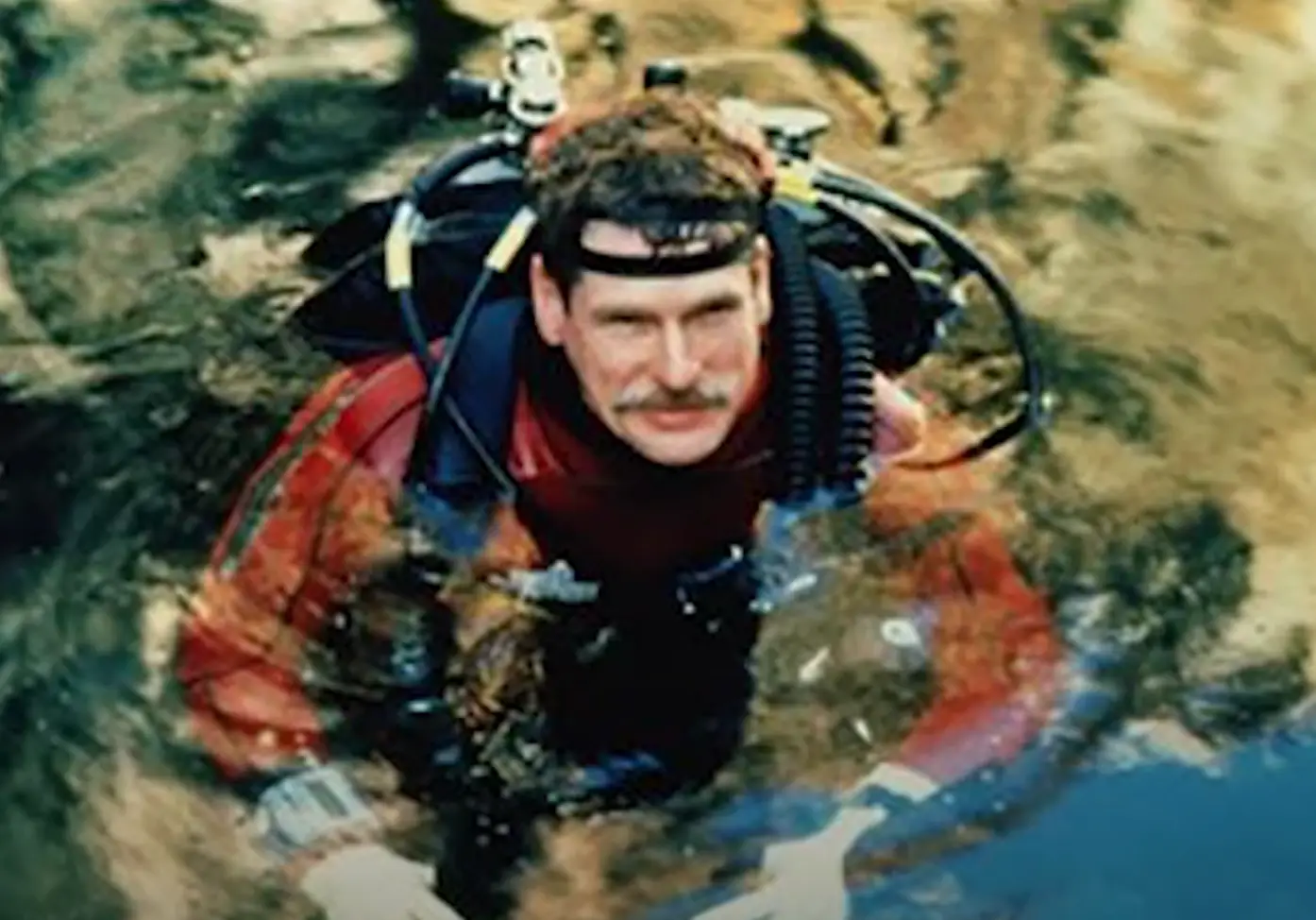

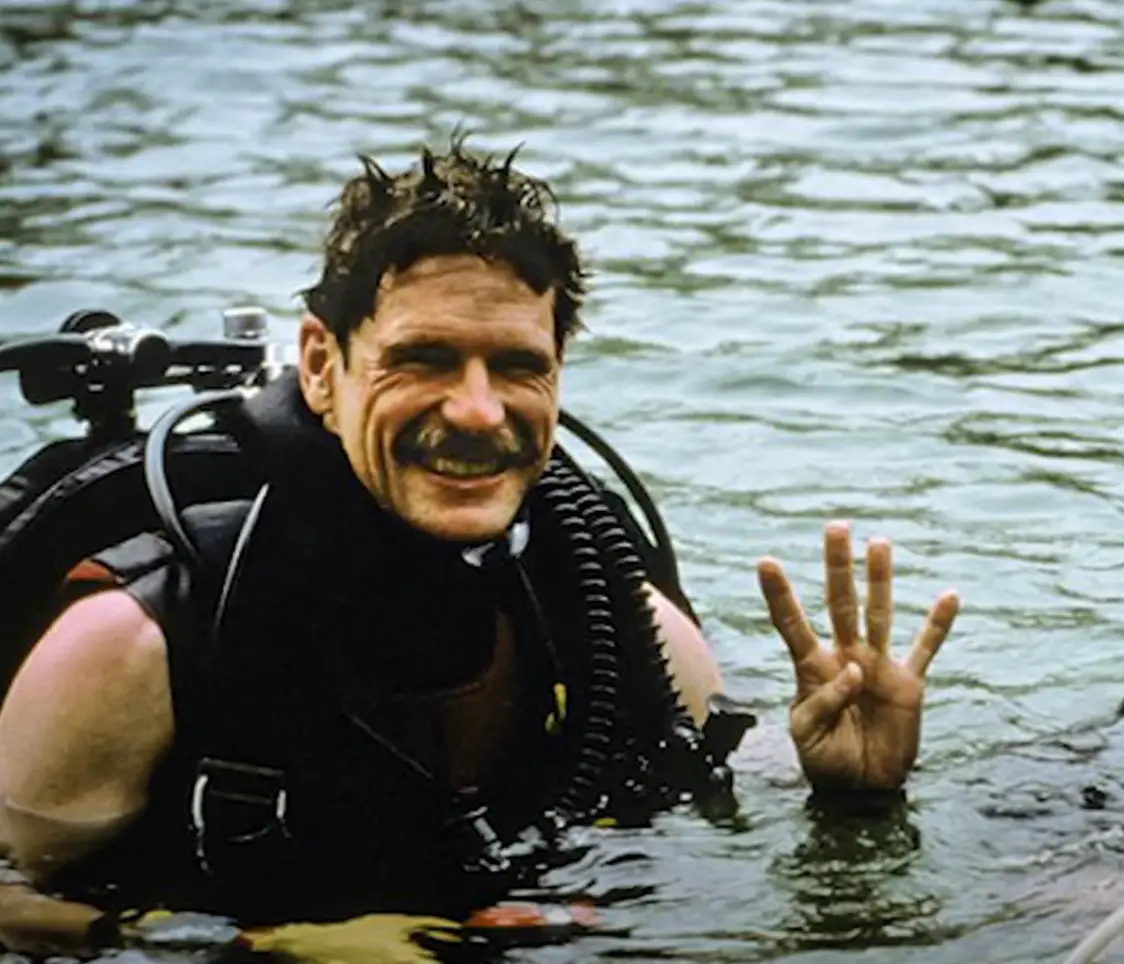

Sheck Exley was a well-regarded name in the cave-diving community, and is known as the first director of the Cave Diving Division of the National Speleological Society.

The legendary diver, who started diving aged just 16, made his way to Zacatón with Bowden and Walten in 1993 and found out after diving themselves that the cenote was much deeper than initially thought.

They soon found out that it was over 1,000 feet deep and were shocked, as Exley managed to dive to 721 feet, while Bowden reached 504 feet, with both making the deepest ever dives into Zacatón.

The warm water and weather conditions made it a favourable diving spot, with the pair set on plans to return and reach the bottom, once and for all.

In April 1994, they returned to Zacatón and wanted to conquer the task of reaching the bottom, taking two days to prepare the required decompression bottles, individual descent lines and routes required to make the bottom.

On 6 April 1994, they made their way down, with Bowden's wife Karen Hohle, Exley's ex-wife Mary Ellen Eckhoff, and Ann Kristovich, all qualified divers, on hand for support, while the landowner and media were present too.

Making their way into Zacatón, they focused up and began their descent on their own lines, though Bowden started to slow down at 750 feet, though after reaching 900 feet, he realised he used more air than planned and had to stop.

After a slight panic with his cylinder valve on the regulator, he managed to see light through the darkness, spotting Exley's line, though he and the team had a feeling that something wasn't right.

15 minutes after they made the dive, only one set of bubbles remained.

Exley's ex-wife Mary knew something was wrong and made her way down in her diving gear, but couldn't find Sheck anywhere.

Bowden was told the news at 60 feet that Exley was gone, and knew there was no recovering him at that depth, and three days later, the team pulled up the remaining line and found Exley's body attached to it.

So, what happened?

It is said that in his final moments, he knew he wasn't going to make it and didn't want anyone risking their lives coming for his body, so tied himself to the line so that his body would be recovered safely.

The diving community was shocked and the man that created many of the safety rules that divers follow today fell victim to the activity he loved most.

But Exley made huge strides for the diving community, setting foundations for many to explore sinkholes, seas and oceans for decades to come.